For the past two lessons, we have been learning how to observe a biblical text. In a survey, you try to observe the book in which a passage is found or perhaps a larger section of biblical text. In Lesson 3, we learned how to observe the details of a passage, a skill sometimes called “detailed observation.”

The final stage of observation is to ask questions. We pretend like we know nothing and ask questions about everything without answering them just yet. These include questions of definition, how questions, why questions, and questions about the implications. Questions of definition range from, “What does this word mean?” to “Who was this person?”

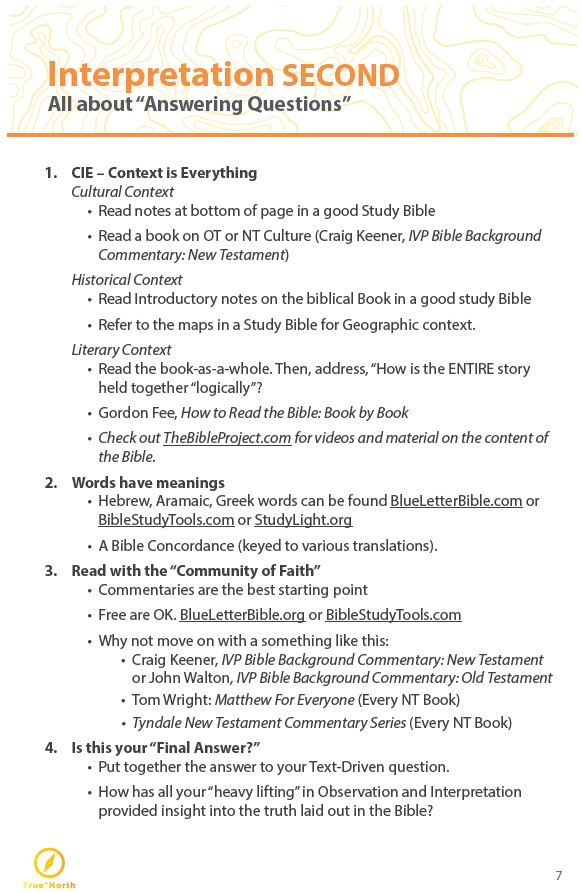

Now in this lesson, we get to interpretation proper. That’s where we do research to try to answer these questions using evidence from the text itself and from historical and cultural background. Observation asked, “What does the text say?” Now in interpretation, we ask, “What did the text mean?” To figure out this original meaning, we will draw evidence from the context.

“Context is everything,” the saying goes. Whether you know you are doing it or not, you read the words of the Bible against some context in order to find meaning in the words. Our default is to read the words in terms of our own context. That’s probably what we are doing if we don’t know anything else, reading it in terms of our own world.

In the downloadable PDF, Dr. David Smith mentions three contexts we need to engage if we are to read the books of the Bible in their original contexts. Literary context is the context of a book of the Bible itself – the other words in the book. Historical context not only may include the various aspects of history that the book engages but also the situation that gave rise to the writing of the book. Finally, Dr. Smith mentions cultural context. This context is a little more subtle but has to do with the various assumptions and worldviews not only assumed by the book but engaged by it.

The literary context is the world within the text itself. It starts with the first word of the book and continues until the last word.

Note: Matthew is not part of the literary context of Revelation. Isaiah is not part of the literary context of Romans. These books were not written by the same authors, with the same exact style or vocabulary, or with the same exact perspectives. This is the wonder of inspiration. God spoke through a choir of voices – not with a single monotone.

Indeed, some of the tensions and alleged contradictions in the Bible are simply different authors using words in different ways. Paul and James do not disagree on faith and works – they just use the words slightly differently (cf. Rom. 3:28; James 2:24). Mark and John do not disagree about Jesus’ use of signs – they just use the word sign differently (cf. Mark 8:12; John 20:30).

Revelation was originally written on an individual scroll. The original meaning of the “do not add or take away” passage at the end (Rev. 22:18-19) only referred originally to the individual scroll of Revelation. That is not to say we cannot read those verses in relation to the rest of the Bible – God knew Revelation would end up as the last book when the scrolls eventually were bound together in a book form. It’s just that John of Patmos give us no sense that he understood or meant that originally. That way of reading the words goes beyond the original meaning of Revelation to John and his audiences. It adds meaning to Revelation itself.

Isaiah is part of the historical context of Matthew. They were not originally written in the same document. Matthew engages Isaiah, a scroll that was written hundreds of years earlier. Understanding these nuances is part of the process of learning how to read the Bible in context, for what it actually meant.

When I am answering questions about the original meaning of a verse in Esther, I gather literary evidence from the rest of the book of Esther. If I am answering questions about the original meaning of Romans, I gather literary evidence from the rest of the book of Romans. Each book may have its own way of using words, so each book should be allowed to speak for itself.

You can do this rather scientifically, if you want. You might create a table with two columns. You might call the left hand side, “Evidence.” Then on the right hand side, you might write, “Possible Implications.” As you collect evidence from the literary context, begin to formulate hypotheses. As you continue, keep a sense in the right hand column of how your hypotheses are doing. Are some eliminated as you keep going? Do some seem to get stronger?

Remember, literary context is only one of the contexts. Don’t draw a final conclusion until you have examined all the contexts.

Genre

The concept of genre is part literary and part historical. Genres are historical because their nature can vary from time to time and place to place. For example, the criteria for historical writing today is in some ways different from the approach in the ancient world, and even in the ancient world, different story-tellers had different approaches.

Genre is also literary in the sense that the reader of a letter knew the basic format of a letter. Speeches in Greek took on particular forms when they were aiming to do different things. Hebrew poetry used a pattern known as “parallelism.” We don’t even have the literary form known as an “apocalypse” today, so it is no wonder that we have trouble understanding the book of Revelation.

Understanding genre is another key element in being able to read the books of the Bible for what they actually meant when God first inspired them for their original recipients.

When Revelation 17:9-11 talks about seven hills with seven kings, any first century reader would no doubt have thought of Rome and its emperors. This is even more likely given that Revelation talks about an evil force in the world that it calls “Babylon” (Rev. 18:2). Babylon was a code name for Rome in some Jewish literature of the time (e.g., 4 Ezra 15:46; Sibylline Oracles 5).

As a modern reader, you have no way of knowing these things unless you discover them somehow. The information is not in the text of Revelation. It is a historical assumption of Revelation that would have been known by its original audiences. This is historical background information. You cannot understand what the text first meant unless you somehow learn these things.

Essential historical and cultural information needed to interpret the Bible is far more the assumption of the biblical text than explicitly stated. The authors and original audiences of Scripture did not need to be told them because they were commonly known and were a common framework of assumptions. You don’t have to explain to your mother who you are in a letter.

Where can you find this information? You can find it Study Bibles. You can find it in commentaries on the books of the Bible. One helpful resource is the IVP Background Commentary, which aims to provide you with background information that you would otherwise have no way of knowing from the text itself. We should also remember that the ancient world has only left us a fraction of its information. Unfortunately, sometimes we just don’t have enough information to know with certainty what some passages in the Bible meant originally.

As with literary context, you can approach the evidence from historical, situational, or cultural context somewhat scientifically. In a left hand column, list possible evidence from history or culture that might have implications for the meaning of your passage. In the right hand column, draw possible inferences and conclusions from the evidence you are finding.

The challenge is that we only have selective information from the past – typically from the wealthy elite. The ordinary people, the ones who did most of the living and dying in ancient Israel and the early church, have left little memory of themselves to history. And even though the information we have is very selective, it is still massive to sort through.

The potential result has sometimes been called “parallelomania.” You find some obscure similarity between a shred of evidence in some random piece of literature that has happily survived. Then you connect it to some small bit of biblical text. Scholars sometimes know too much and find parallels between what turn out to be completely unrelated things.

Let’s say an archaeologist digs up a vacuum bag 500 years from now. Then let’s say that same person reads a 21st century novel that calls someone an “old bag.” We know right now that these two things have nothing to do with each other. But that archaeologist 500 years from now, going on sparse surviving evidence, might make a connection. You can hear them, “In the early twenty-first century, people sometimes called each other ‘old bags’ like a suction tool they used to do to clean cloth that they put on their floors. Perhaps such people had a tendency to be exhausting, like a machine that sucks the wind out of you.” No doubt much of our biblical interpretation would be this strange (and comical) to the biblical writers if they were to read it.

Situations

Probably the most important historical information we could have about the biblical texts would be the situations under which God inspired them to be written. Again, God inspired the Bible for us and for all time. However, in the moment of their writing, God inspired them to communicate to specific audiences in specific situations. This dynamic affected their original nuances.

It is often said that Paul’s letters were “occasional,” meaning that they were written on specific occasions. And God inspired Paul to speak to those occasions. If you have more than one child, you know that their personalities are all unique and distinct from each other. So it is no surprise that God tailored the messages of these letters to their audiences. The Galatians are too strict, so Paul tells them to loosen up. The Corinthians are too loose, so Paul tells them to tighten up.

If we do not know these situations, it would be easy to misapply the teaching and instruction to today. As we will see in the final lesson, this makes applying the biblical text a careful task, one that we should do in a community of faith, with fear and trembling (Phil. 2:12). The challenge is particularly acute because we do not exactly know the situations of many books of the Bible. Scholars spend lifetimes of study in dialogue with each other trying to determine answers to these questions, and they still frequently disagree with each other.

It is often said that a fish may not be aware that it is swimming in water just as we normally do not pay much attention to the air around us. Culture is like that. We are swimming in it but probably not very aware of it. Culture shapes us from our youngest moments. It forms our unexamined assumptions about what is normal.

There is no such thing as humanity outside of human culture. Is it normal to laugh out loud for no reason in a restaurant? Do you say, “Bleep, bleep” to someone you are passing on a sidewalk? Should you walk on the grass next to a sidewalk or on the sidewalk itself? Is a ladder a common living room decoration? You can see that we can easily find those who do not understand or practice the rules of our culture funny, annoying, or even infuriating… and we may not be able to say why!

The Bible is “incarnated” revelation. As Jesus took on our flesh and became fully human (John 1:14), revelation comes in language and categories that its recipients can understand. That is to say, since there is no human interaction or communication outside of culture, God inspired the messages of Scripture in the languages and in dialog with the cultural frameworks of its audiences. If he had not, these books would not have been meaningful to their intended recipients. They would not have received a word from the Lord. In that sense, every word of the Bible is “cultural.”

We will inevitably read our own cultural assumptions into the Bible if we don’t know any better. If we come from an individualistic culture (which, if you are taking this course, you probably do), you will read the books of the Bible individualistically. You might easily miss the communal and community dimension of the texts. Individual, adult baptism will make sense to you. An entire family being baptized in Acts 16:15 will seem strange.

Are you from a culture where authority is no big deal or families are not close? You may not quite get the respect the Bible expects in relation to elders and leaders. You might assume that biblical families were husband, wife, and children rather than extended families with aunts, uncles, and cousins. Do you come from a money economy? You might miss some of the agrarian and trade dynamics of the biblical worlds.

If we want to hear the biblical words on their own terms as God first inspired them, we will need to learn some of the cultural features of the biblical worlds. And we remember that God inspired the Bible over a thousand year period. The culture of the patriarchs was not the culture of the monarchy of Israel or the time after the exile, and none of these were the culture of the Mediterranean world under Roman rule.