The story of Martin Luther in the early 1500s has been told many times. He was an enthusiastic monk, a true believer. He visited Rome in 1510. Instead of finding a holy place where God was the focus, he found a worldly place focused on money and power. He was disgusted.

The last straw was in 1517 when a traveling “indulgence salesman” came through town. For some background, one of the new beliefs that arose in the Roman Catholic Church in the late Middle Ages was that of purgatory. Purgatory is an imagined place where Christians who have sins that need to be “burned off” go until they are purified enough to go to heaven.

Indulgences were allowances from the Pope to get years off of purgatory. Pope Leo X had approved the sale of “years off” purgatory in exchange for donations to Rome so that they could build St. Peter’s Basilica, which still stands at the heart of Vatican City. Johann Tetzel, a monk, came through Wittenberg where Luther taught, selling these indulgences: “Every time a coin in the coffer clinks, a soul from purgatory springs,” or something along those lines in German.

Indulgences were allowances from the Pope to get years off of purgatory. Pope Leo X had approved the sale of “years off” purgatory in exchange for donations to Rome so that they could build St. Peter’s Basilica, which still stands at the heart of Vatican City. Johann Tetzel, a monk, came through Wittenberg where Luther taught, selling these indulgences: “Every time a coin in the coffer clinks, a soul from purgatory springs,” or something along those lines in German.

On October 31, 1517, the night before All Saints Day, Luther nailed 95 debate points, 95 Theses, on the door of the Wittenberg Castle Church. The rest is history. Some of his friends took them down and used the newly invented printing press to make many copies to distribute. Obviously, he hit a nerve. They were translated from Latin into German and other languages. They were widely disseminated throughout Germany and then Europe, sparking widespread debate and controversy.

The Catholic Church did not immediately respond, but Luther’s Theses went viral. They hit on a sentiment that was widespread but without a clear path to be expressed. Rome was felt to be corrupt and political, lacking the very virtue of which it was meant to be the central representative. Soon church authorities became concerned. In 1518, Luther was summoned to Augsburg by the papal legate Cardinal Cajetan to recant. Luther refused.

In 1519, Luther participated in a public debate with Johann Eck at Leipzig. This debate helped clarify and solidify Luther's views, pushing him further towards a break with the church. Like so many reformers, he did not initially set out to break with the church. But Luther’s understanding of Scripture was deeply at odds with what the Church of Rome had come to believe. He did not believe the Pope had the authority he claimed to have. Luther did not believe that good works had anything to do with salvation, while the church believed both were essential. The cornerstone of his protest was the doctrine of justification by faith, the sense that the Bible teaches we can only get right with God (be “justified”) by faith in Jesus Christ, not by any works we might do.

In 1520, Pope Leo X issued an official decree (a “Papal Bull”) threatening Luther with “excommunication” unless he recanted his positions. In theory, excommunication would mean that Luther could not go to heaven. But Luther did not think the Pope had the authority to keep anyone out of heaven. Luther responded by publicly burning the bull and other books of church law. So the Pope excommunicated Luther in January 1521. Luther was now officially a heretic.

Now the Holy Roman Emperor got involved, the chief political authority in all of Europe. Charles V demanded that Luther recant at a meeting called the Diet of Worms (a “Diet” in this context was an assembly called to make important decisions; Worms is the city in Germany where the meeting was held). Luther famously stated, “Here I stand; I can do nothing else.” Now Luther was declared a political outlaw, with his writings banned.

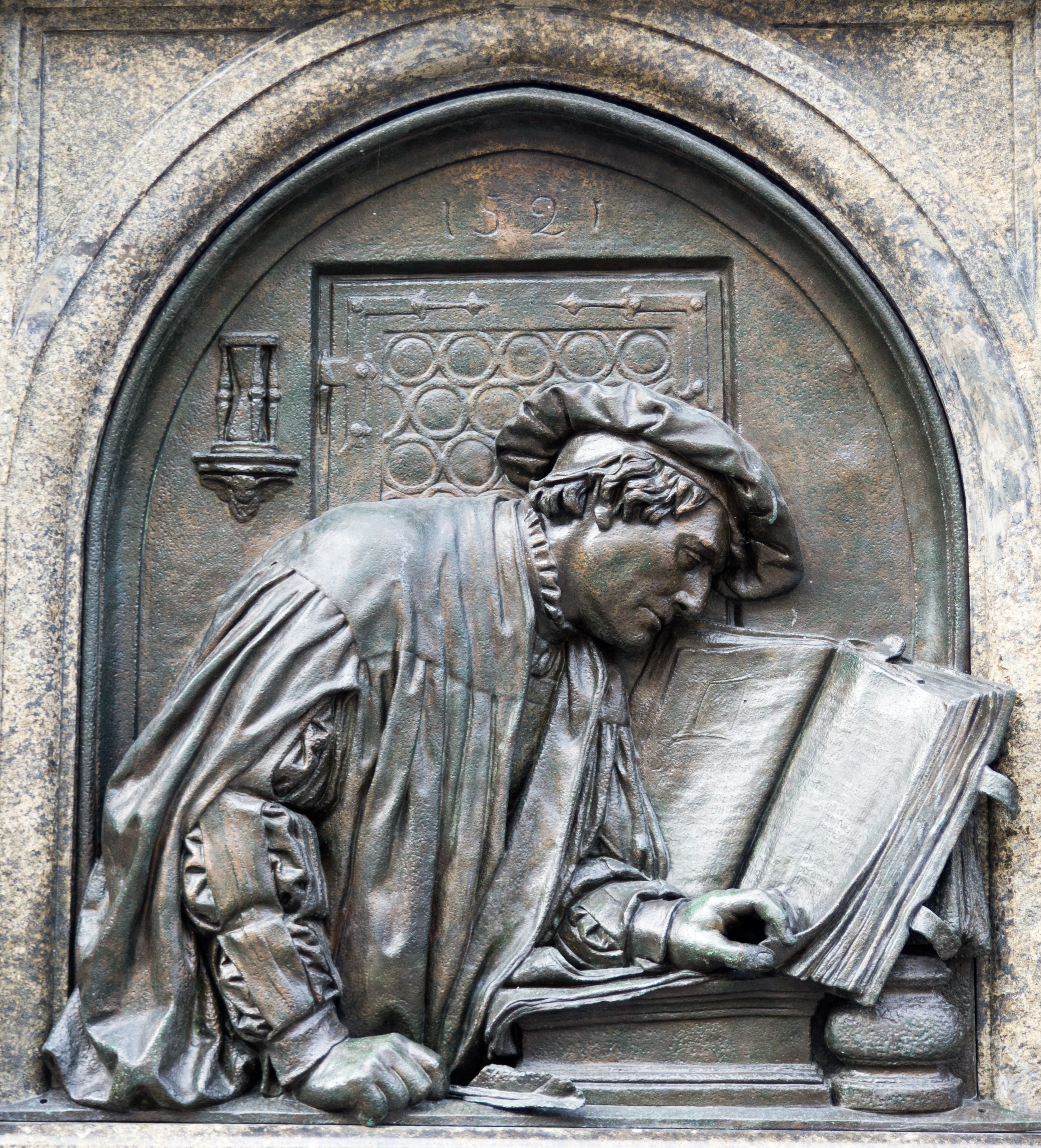

Again, Luther hit a nerve. If there was a grassroots sense that the Roman Catholic Church was corrupt, the Empire also was not strong enough to stop support for Luther. One powerful “elector” in the empire “kidnapped” Luther and hid him in his castle for a year. During that year, Luther began to translate the Bible into German – which was prohibited. This insistence that the Bible be in Latin was yet another development of the late Middle Ages in the Roman Catholic Church.

The Reformation had begun. “The Reformation” is the term used for the movement that Martin Luther started. Luther and others were called Protestants because they were protesting against abuses in the Roman Catholic Church, as well as against teachings and practices that they believed were contrary to Scripture. Theirs was a call back to the Bible, to turn back the clock on a number of teachings that had chiefly accrued in the late Middle Ages. For example, Luther married a nun in 1525, defying the church’s requirement that priests be celibate. Luther could not find any basis for that requirement in Scripture.

The Five “Solas”

The Latin word sola means “only” or “alone.” Over the course of the Reformation, five of these Latin expressions emerged as a summary of the “protest” Protestants were making against Roman Catholic teaching and practice.

Sola scriptura asserts that the Bible is the only infallible source of authority for Christian faith and practice. This principle emerged as a response to the Roman Catholic Church’s elevation of church authority and tradition equal with the Bible. Martin Luther, in his disputes with the Catholic Church, emphasized that Scripture is the only standard by which all teachings and traditions of the church should be measured.

He did not mean to negate the importance of church tradition and the church’s teaching. Rather, he wanted to make sure church authority was subordinate to Scripture. Luther argued that the Bible is clear in its meaning and accessible to all believers, not just the clergy or theological scholars (called the perspicuity of Scripture). This emphasis on the Bible led to the translation of the Scriptures into vernacular languages and promoted widespread literacy, as people were encouraged to read and understand the Bible for themselves.

At the same time, Luther felt free to question the contents of Scripture. The idea of “faith alone,” the next sola, was so strong that he almost didn’t translate the book of James into German. He considered it an “epistle of straw” because of its emphasis on works. Luther also moved several books that had long been integrated within the Old Testament to the end. He labeled them as Apocrypha (hidden), by which he meant they should not be read in public worship.

Some in the Wesleyan tradition have spoken of a Wesleyan Quadrilateral in which Scripture plays the central role accompanied by significant input also from tradition, reason, and experience. This model is thought to derive from observing how John Wesley arrived at theological conclusions. It has been described as “prima scriptura” or “Scripture first.” However, others in the Wesleyan tradition have rejected this description of Wesley’s theological method.

One of Luther’s primary sparring points with the Roman Catholic Church was over how a person came to be saved. In his struggle with Romans 1:17, Luther eventually came to conclude that the center of the good news was that our right standing with God was a gift, not something any of us could earn by good works. Ephesians 2:8-9 was key: “For it is by grace you have been saved, through faith—and this is not from yourselves, it is the gift of God—not by works, so that no one can boast.”

Luther and then later Calvin did not believe that we have any role in coming to faith. For them it is purely a matter of God’s predestination alone (“monergism”). In their minds, any role on our part would make faith work. By contrast, John Wesley and others later believed that God empowers us to move toward faith: we can respond positively, with God’s will and our will working together (“synergism”).

Sola gratia goes hand in hand with sola fide. It is the belief that salvation comes by grace alone and not through any merit on the part of the sinner. This grace is seen as the unmerited favor of God towards sinful humanity. Luther’s understanding of grace was shaped by his interpretation of Paul’s letters, where the concept of grace is a recurring theme.

The doctrine of sola gratia as Luther meant it asserted that God initiates and completes the work of salvation. For Luther, it was God’s action from first to last. This was a significant shift from the prevailing view of the time that human beings played a cooperative role in their salvation by combining their merits with the merits of Christ’s death on the cross. Note again that Wesley, by contrast, believed in prevenient grace, by which he meant a grace that comes to us and eventually enables us to exercise faith. Wesleyans thus believe that we do exercise a cooperative role in coming to salvation, but only as a response to the grace God freely offers to all individuals.

Solus Christus emphasizes that Jesus Christ is the only mediator between God and humanity. This principle was a response to the Catholic practices of venerating saints and the clergy acting as mediators in the forgiveness of sins. Luther and the reformers asserted that salvation is accomplished through the work of Christ alone. His life, death, and resurrection were sufficient for the salvation of humanity. No earthly priest is needed for salvation, but we are a “priesthood of believers” (1 Pet. 2:9).

This doctrine is deeply Christocentric, focusing on the person and work of Jesus Christ as central to the Christian faith. It rejects the idea that any human, whether a priest, saint, or religious figure, can mediate or add to the redemptive work of Christ. This principle led to a reevaluation of church practices like the veneration of saints, the role given to the Virgin Mary, the authority of the priesthood, and the nature of the sacraments.

Soli Deo Gloria is the teaching that all glory is due to God alone, as everything is done for His glory and not for human praise or favor. This principle served as a corrective to what the reformers saw as the church’s focus on human achievements and the glorification of church leaders. It emphasizes that salvation, and indeed all things, are to result in the glory of God, not the exaltation of humans.

This sola is often seen as the purpose and summary of the other four. It directs all attention and praise to God, recognizing that everything from salvation to daily living is an opportunity to glorify God. This principle had a profound impact on Protestant worship, theology, and cultural engagement, emphasizing that every aspect of life is to be lived under the lordship of Christ and for the glory of God.