We tend to think of the Bible as if it was just there from the beginning. It’s almost as if we think the Holy Spirit passed out New Testaments on the Day of Pentecost for everyone to read. This dynamic is part of our tendency to read the books of the Bible out of context, as if the words had nothing to do with the situations they addressed or the language of the time. We treat the words of the Bible as if they exist in a bubble, just for me.

We can gain great insight by tracing the path by which these books came to be affirmed as the New Testament. Not only does it help us gain a greater appreciation for the Church, but it also helps us begin to understand how history has shaped so much of what we think and understand without us even knowing it. It may be surprising that the first time we know of someone listing the exact books that are in our New Testaments as the right books was not until the year AD 367 in an Easter letter by none other than Athanasius!

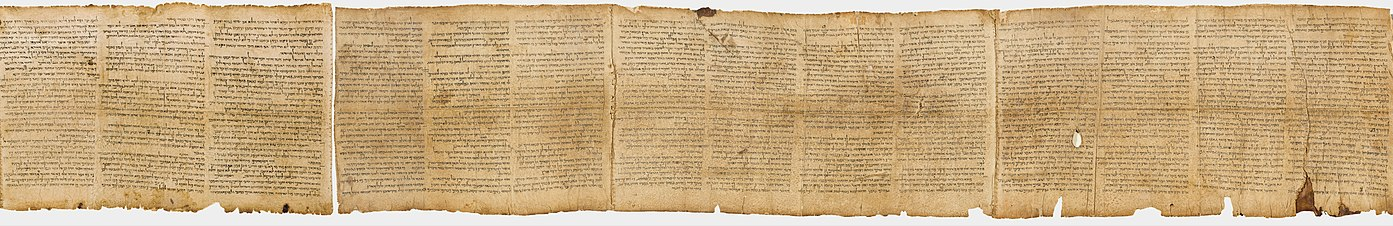

Scroll of Isaiah - high resolution image available at Wikimedia Commons

The canon refers to the authoritative collection of books in Scripture, coming from a Greek word that referred to a measuring reed. The New Testament canon began, of course, with the writing of the books. This took place over several decades as these books were written in various places by various authors with differing writing styles addressing different contexts and situations. We believe that the Holy Spirit inspired these writings while also affirming that God did so using the personalities, writing styles, and distinct perspectives of the authors. The result is a rich chorus of inspired voices rather than a monotone chant.

Paul’s letters were likely the first books written. They are listed in our Bibles today from longest to shortest, not in the order they were actually written. 1 Thessalonians or Galatians was likely the first book of the New Testament written. Paul died in the 60s under the Roman emperor Nero, so all of his books were written by then (although there are some scholars who think some were written after his death).

James and Peter also were put to death in the 60s. That suggests their writings were written before then. It is harder to date Jude. If 2 Peter 2 used Jude as a source, that would suggest Jude was also written before the late 60s.

It is generally agreed that Mark was the first of the Gospels written. This idea may be surprising. For one thing, the fact that Jesus came first may unthinkingly lead us to think the Gospels came first, but what a book is about is a completely different thing from when it was written. After all, books are still written about Jesus today! Mark is generally dated to the late 60s or early 70s.

Most scholars think that the Gospels of Matthew and Luke used Mark as one of their sources. This fact suggests that Matthew was not written until the 70s. Luke-Acts, then, may have been written in the 80s. The fact that Acts ends without telling us what happened to Paul does not clearly tell us when it was written. Just because we don’t know how the story ended doesn’t mean that they didn’t know. John is traditionally dated to the 90s.

Revelation is also traditionally dated to the 90s. That leaves 1, 2, and 3 John. Since their flavor is similar to the Gospel of John, we might date them to the late first century as well.

Grouping of Books

Interestingly, 2 Peter implies the collection of Paul’s writings as Scripture (3:15-16). This is quite remarkable because it would suggest the beginnings of a new canon as early as the 60s. (Some scholars have also suggested that 2 Peter was written later.) 2 Peter is clearly evidence that Paul’s writings were brought together into a collection early and were understood to have distinctive authority.

Around the year AD 160, a man by the name of Tatian created a “harmony” of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. A harmony is when you put the four accounts side by side or integrate them together into one continuous account. This spliced-together version, called the “Diatessaron,” implied that those four Gospels were considered Scripture already by that time. In fact, Tatian’s Diatessaron was actually used as Scripture for a few centuries in Syria.

In the late 100s, a church father named Irenaeus argued that the idea of four Gospels had merit for several reasons. Some of them may seem a little peculiar to us today, such as the argument from the fact that there are four corners to the (flat) earth, serving like the directions of a compass. What is more important is that he shows that mainstream Christians in the late 100s believed that these four Gospels were the authoritative ones. Meanwhile, Irenaeus was implicitly denying that other Gospels at the time were legitimate, like the Gnostic ones.

The bulk of the canon was thus in place by the end of the 200s. An important fragment from around the year AD 200, called the Muratorian Fragment, mentions as authoritative most of the books that are currently in our New Testaments. It is a fragment, so we cannot be entirely sure of what it contained, but most think it did not include Hebrews, James, either of the books of Peter, or 3 John. At the same time, it had a number of books that did not end up in the New Testament: the Apocalypse of Peter, the book of Wisdom, and letters attributed to Paul to the Laodiceans and Alexandrians. The Shepherd of Hermas (ca. 150) is mentioned.

Criteria for Canonicity

Criteria for Canonicity

1. apostolicity – Was the writing connected to an apostle?

2. antiquity – Does the writing go back to the earliest church?

3. orthodoxy – Does the writing fit with the rule of faith?

4. catholicity – Is the writing widely used in the Church?

As Christians wrestled with which books were authoritative, several criteria emerged. One was a connection to an apostle or apostolic authority. Paul’s writings clearly passed, as did those of John. Mark was connected to Peter and Luke to Paul.

Questions over Hebrews, James, and 1-2 Peter were thus connected to the question of their authors. Was Paul the author of Hebrews? Many in the west did not think so, while easter Christianity was more quickly convinced. Many were not sure whether Peter was really the author of 2 Peter, making it one of the last books to enter the canon.

Implied in the connection to an apostle is a sense of antiquity. There were other writings that were true and even inspirational (as there are today), but they did not go back to the original apostles and were not ancient enough. 1 Clement was a fine letter, but it was written in the late first century by someone who was not an apostle.

It was, of course, also important that the book fit with the rule of faith mentioned above, that it be orthodox. Some might have questioned Hebrews because it sounded like you couldn’t repent if you fell away. Some questioned Revelation because of its strangeness. Several Gospels authored by the Gnostics did not pass this test.

Finally, was the writing used throughout the Church, not just in some corner. Tatian’s Diatessaron was only used in Syria. The Gnostic Gospels were mainly used in Egypt. The use in worship was important. The Muratorian Canon suggests that the Shepherd of Hermas only be read at home, not in church.

Over time, the Church reached a consensus on the contents of the canon. Interestingly, it did not need a council to ratify it. There were some smaller councils in the late 300s that affirmed our current list, but they were not universal councils. The first time we know of when someone mentioned the same exact list of books that is now in our Bibles was an Easter letter by Athanasius in the year AD 367.

So the formation of the New Testament canon was not an event but a process that unfolded over several centuries. It came from an interplay of good theology, church authority, and down-to-earth use in worship and teaching. The canon that emerged was not arbitrarily chosen but grew organically out of the life and faith of the early Christian community. If we are to believe in the New Testament, we must believe that the Holy Spirit was at work in the Church too.